Navigation auf uzh.ch

Navigation auf uzh.ch

At Kilvey Hill, once the site of steaming copperworks and now an idyllic, undeveloped recreational area, plans are underway to build a cable car and other leisure infrastructure. This has sparked resistance from the local population, who had reclaimed the former industrial wasteland through extensive volunteer efforts. Can this hill tell us anything about possible futures after deindustrialization – and about disputes over these futures?

Figure 1: Chimney of the former Hafod Copperwork. Photo by author.

On the third morning of the trip, after spending two days touring sites of the coal and steel industries in South Wales, we found ourselves meeting with researchers and students from Swansea University for an exchange meeting. Participants from both groups presented examples of industrial rise and decline in Wales and Switzerland. The afternoon was reserved for individual, exploratory field research. In preparing the trip, I had chosen the topic "Industrial Traces in Today's Urban Space." This seemed relevant to my previous readings and seminar presentation on nostalgia and forms of memory. I had found some readings particularly useful: a text by historian Stefan Berger on “regimes of memory” in a global comparison and the concept of “agonal memory” by historian Anna Cento Bull and literary scholar Hans Lauge Hansen.[1] The latter apply political theorist Chantal Mouffe’s concept of the agonal principle to regimes of memory. They distinguish three different ways society deals with sites of memory: antagonistic, cosmopolitan, and agonal memory. Broadly sketched, antagonistic memory involves the destruction (mostly from “above”) of memories of defeated groups. An example is the time of market-radical forms of deindustrialisation seen in Britain during the Thatcher era, when the importance and power of trade unions was actively weakened and elements of popular memory such as “solidarity within the working class” were downplayed or even erased. Cosmopolitan memory in deindustrialisation contexts, according to Berger, is more common under corporatist socio-political conditions, i.e. a stronger integration of representatives of different societal groups and classes. It involves a certain level of consensus among the governing and the governed, a recognition of workers' and industrial history, and the invocation of universal values. Berger cites the handling of deindustrialisation in the Ruhr area, shaped by the Rhineland capitalism of West Germany, as an example. The Zollverein Coal Mine Industrial Complex, for instance, is now a museum, cultural, and meeting place where the past is publicly remembered. According to Berger, these two forms of memory serve hegemonic purposes, albeit in different ways. The agonal principle, on the other hand, opens up a discussion about memories without seeking to pacify them by suppressing or celebrating them: A self-reflective culture of memory and a democratically defined, future-oriented struggle over the past thus make it a subject of competition for different futures. Agonal memory can serve, then, as a tool to question present processes with the help of the past.

Historian Sarah May offers a slightly different perspective on this in her reflections on the cultural heritage of the Anthropocene.[2] She ponders the industrial, and thus human, legacies on the planet. She wonders whether sites of industrialisation could also be read as "dark heritage" – as the epicenter of the Anthropocene. And finally, she asks whether tourism and memorial sites that replace industries are sustainable or would lead to ruin again.

With these topics in mind, I set off for my afternoon of field research, i.e. a long walking tour. Dr. Hilary Orange from Swansea University mentioned in conversation a memorial site of copper mines near the city center on the banks of the Tawe, at the foot of Kilvey Hill. The area, where copper was once mined, is currently undergoing major urban transformation, with debates over the construction of a cable car on the hill. Memorial sites of vanished industries? Possibly disputes over potential futures? Off we go.

On the bus to Copper Quarter, I did some quick reading on the copper industry in Swansea and Kilvey Hill: Before the coal boom, copper was the first major heavy industry in Wales, starting in the 18th century, with the Tawe Valley and Swansea asits epicenter.[3] This was possible due to the availability of coal needed for smelting metals. Copper ore was delivered to the city's port, and copper sheets were shipped worldwide. With the decline of the copper industry after the Global economic crisis in the late 1920s and World War II, what remained was the largest industrial wasteland in Europe at the time.[4] In the early 1960s, the Lower Swansea Valley Project initiative by the government and Swansea University aimed to reclaim the contaminated land. Over more than twenty years, schoolchildren and local volunteers were involved, for example, in planting trees and shrubs.[5]

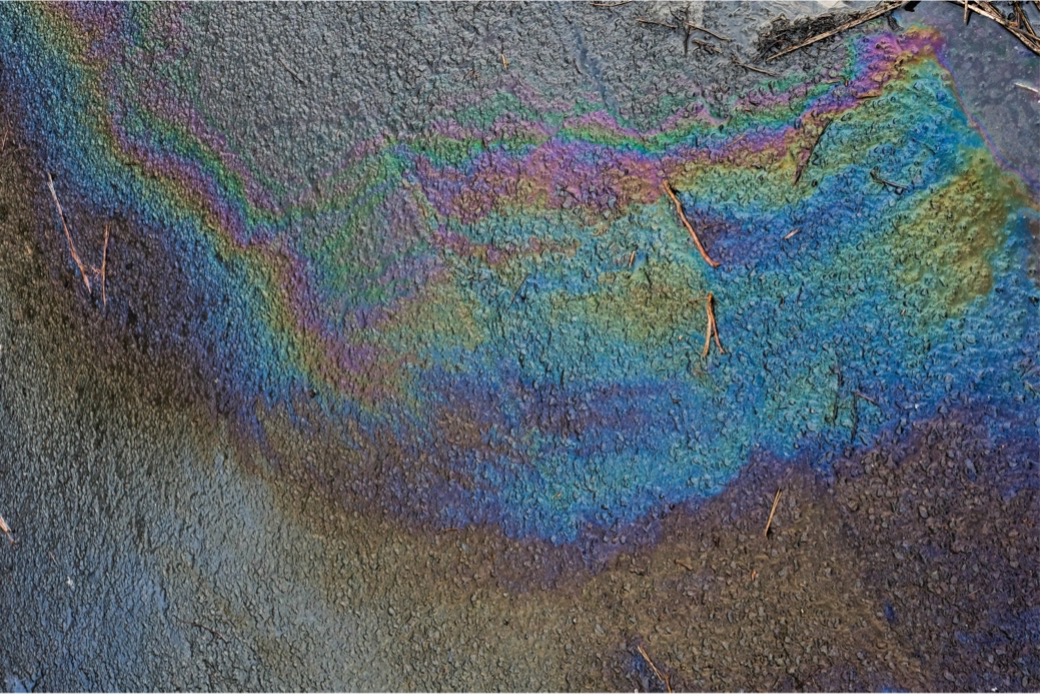

From the bus stop, the path leads slightly downhill to the Tawe River. Behind me is the residential area Mayhill, covered with houses, opposite the undeveloped, wooded Kilvey Hill. The valley area is heavily populated: new housing estates, a shopping center, various small businesses, a football stadium. At the foot of Kilvey Hill, a small, unpopulated hilly landscape is visible. And I see two tall chimneys. There must be something there. On the way to what I think is the memorial site, I end up on the Industrial Heritage Trail. Small, laminated papers with arrows on posts indicate the way, and a large wooden board – edged with copper – features the emblem and inscription of Hafod Copperworks, one of the largest copper giants of yesteryear. Further along the path are various stone sculptures showing work scenes from the copperworks cast in ceramics. Around them are English and also some Welsh words embossed. According to DeepL, they can be translated as dirt, toil, lubricant, stink, strive, sizzle. On another information board, the history of the copper industry and an aerial photograph of the Swansea Valley are displayed, including a "You Are Here" point.

Of the entire former Hafod site, only the heavily dilapidated power plant and laboratory buildings remain. They are listed buildings, as I learn from my reading, and temporarily secured from decay with structural measures. Money for restoration is lacking.[6] The old brick houses seem somewhat rebellious to me, enclosed by a tall, graffiti-decorated metal fence. Next to it, the path leads past towards the river. Hilary Orange mentioned in the morning that the last larger, still undeveloped area is a popular recreational area for the people of the city. Many also have personal memories of the area's renaturation. On the meadow across the river, I see people walking dogs.

Resistance has now formed against plans of the New Zealand company Skyline Enterprises Ltd which promise – or threaten – to shape the future of this site.[7] The company plans to use the natural and undeveloped hill for leisure activities with a cable car and, among other things, a zipline.[8] The £40 million project promises, according to the company, 100 jobs and a boost for local tourism. Whether the project is to be built will be decided by the authorities.[9]

A Sunday before my walk on the hill, where I am now, a rally with about 300 people took place at the summit of the hill. Some posters are still there, with slogans like: "Don’t Kill Kilvey Hill", "Our Big Day Out On Kilvey Hill", or "<3 Kilvey <3 Big Day Out". The Open Spaces Society, which advocates for publicly accessible forest and meadow areas, also opposes the project, arguing with Britain's Countryside and Rights of Way Act from 2000.[10] The law ensures public access to forests, paths, and meadows. The dense, green forest is crisscrossed by a loose network of gravel paths. It's difficult to imagine that the air here was hardly breathable two hundred years ago.

Emerging from the forest and reaching the hilltop, the view over Swansea Bay and the Bristol Channel unfolds. To the east on the horizon, the Tata Steelworks plant in Port Talbot is visible. On the day before, we visited the massive steelworks site, which may soon close and cost thousands of people their jobs.

I wonder what is currently being negotiated here on this hill? After and during the decline of the coal industry, the Swansea Valley wasteland – an old, open wound from the copper era – was re-naturalised, or rather healed, by members of the community itself, through initiatives by the city of Swansea and the Welsh government.

The forest and meadow are linked to personal memories for many, reflecting the traces that the spaces of deindustrialisation leave on land and people – in a more positive sense. But fifty years later, the trauma of deindustrialisation also threatens to repeat itself in the region.

Following my walk on Kilvey Hill numerous questions arise:

Considering possible futures, could a solution to the looming economic problems now be the sacrifice of recreational space that had once been reclaimed by the community? In an post-industrial age and an era of events, does recreation no longer take place in undeveloped areas, but only in structured and commercial leisure activities? Would (re)developing this land mean sacrificing the community’s processing of traumas of deindustrialisation? Would the piece of land that the community has freed from the toxic remnants of deindustrialisation and thus reappropriated through manual labor no longer be a "memorial" of these processes? Would the memories of the suffering disappear with renewed development? And finally, would the return to undeveloped land take on a completely new meaning - namely, that of merely preparing for a new cycle of industrialisation?

How should a community deal with the material consequences of deindustrialisation, such as fallow land, in the future? What if, as Sarah May suggests, tourism as a replacement industry ultimately is not a sustainable solution, contrary to what many urban planners seem to think, and is sooner or later inevitably doomed to decline?[11] Do the opponents of the cable car project present a way out of the system (cycle?) of boom and bust? Or is this environmental protection a form of self-protection for the Swansea community in the face of a new, looming trauma, that is only nostalgic and future-averse? Is the fight to preserve the renaturalised landscape or rather the healed wound of a previous phase of deindustrialisation, then, merely a proxy? And if so, then for what? Is it the renewed force of deindustrialization and the loss of jobs and security? Does the renaturalised piece of land, and the memory of its use, stand for self-efficacy or self-empowerment against global forces and processes that seem unstoppable?

Returning to Mouffe's agonal principle of the conflict between different ideas of the future, it could be argued that this view would be based on a rather conservative, defensive idea of the future. But could the memory of the decline of the copper industry – or rather the reappropriation of the piece of land – not also be the framework for an actively designed future? What would that mean for the construction of the cable cars?

In any case, the dispute at Kilvey Hill aligns with agonal forms of remembering: by referring to the past, different possible future scenarios are debated.

[1] Berger, Stefan «Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Nostalgie. Das Kulturerbe der Deindustrialisierung im globalen Vergleich», in: Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History, (2021) S. 94–121.

[2] May, Sarah «Local Heritage – International Impact: Where is the Heritage of the Anthropocene?» in Shaped by Steel: Landscapes, Lives and Legacies of a Global Industry (2021) S. 156–159, Swansea University.

[3] Footsteps Bangor: Swansea, https://footsteps.bangor.ac.uk/de/location/swansea, accessed 16.6.24.

[4] Swansea Museum: The Lower Swansea Project, http://www.swanseamuseum.co.uk/swansea-a-brief-history/industry/the-lower-swansea-valley-projectaccessed 16.6.24.

[5] Lower Swansea Valley Project, https://lowerswanseavalleyproject.wordpress.com,accessed 16.6.24.

[6] BBC Online: Swansea Hafod copperworks preservation begins, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-south-west-wales-24487743, accessed 16.6.24.

[7] BBC Online: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c25llw925zwo accessed 16.6.24.

[8] Skyline Swansea, https://www.skylineswansea.co.uk, accessed 16.6.24.

[9] Government Wales: The sky’s the limit in Swansea for new tourism venture, https://www.gov.wales/skys-limit-swansea-new-tourism-venture, accessed 16.6.24.

[10] Open Spaces Society: Don’t kill Kilvey Hill, https://www.oss.org.uk/dont-kill-kilvey-hill/ accessed 16.6.24.

[11] May, Sarah «Local Heritage – International Impact: Where is the Heritage of the Anthropocene?» in Shaped by Steel: Landscapes, Lives and Legacies of a Global Industry (2021) S. 159, Swansea University.

David Jäggi