Navigation auf uzh.ch

Navigation auf uzh.ch

More than a famous poet, Dylan Thomas stands as a marketable symbol of Welsh culture and identity. Excerpts of his works hang in hotel rooms and pubs. His influence is seen throughout Swansea, from murals and statues to the dedicated Dylan Thomas Centre. Through interactive displays and community programs, the Centre not only honors Thomas's legacy but also promotes a vibrant and inclusive representation of Welsh culture. But how does the poet, writer and actor embody the diffuse national concept of ‘Welshness’?

Figure 1: Dylan Thomas lettering in Mumbles. Photo by Serafina Andrew.

This sea-town was my world; outside a strange Wales, coal-pitted, maintained, river-run, full, so far as I knew, of choirs and football teams and sheep and storybook tall hats and red flannel petticoats […].

– Dylan Thomas (1943, 1953) [1]

The sea town Dylan Thomas writes about in his poem is Swansea. Thomas was born there in 1914 and counts as the most influential Welsh poet of all time. Traces of him, his works, and his persona can be found all over the city: There are excerpts of his work hanging in hotel rooms and pubs, his name appears on decorative graffiti (see figure 1), there is a statue of him at Swansea’s Maritime Quarter – and there is the Dylan Thomas Centre. Similarly to symbols and tropes such as the red dragon, the Welsh language, Celtic forms, and names from history, Thomas is presented by the guardians of local culture as a symbol of Welsh identity.[2] He also stands for Swansea, the city, more specifically. [3] With this in mind, my report addresses questions about Welshness and Welsh identity and how they are depicted in the Dylan Thomas Centre and its exhibition.

Before addressing the Dylan Thomas Center and its exhibition, I will shed some light on the concept of Welshness and its seemingly ongoing identity crisis. As Dan Evans writes, national identity is not an immediate representation of the reality of history and society but needs to be understood as a discursive construct that has been created, then popularised, and contested – this holds true for the Welsh case as well.[4] The discursive construction of Welshness has, he argues, led to two fairly one-dimensional stereotypes, two representations of Welshness embodied in specific (masculine) figures, which Evans terms the “two truths”. [5] Those two truths consist of the image of the “soot-faced miner” (of South Wales) on the one hand – we have seen ample evidence of this in the museums and industrial heritage sites we visited – and the “windswept, Welsh-speaking farmer” (of the rest of the country) on the other hand. [6]

The persistence of the two images and the narratives that surround them, Evans argues, prevent the emergence of a renewed, more diverse sense of identity.[7] Even today, he claims, Welshness and Welsh identity are strongly linked to stereotypical ideas of (rural) Wales and the Welsh language. [8] This may lead to a feeling of exclusion, especially among minority groups and women who do not identify with this idea of a male-connotated, white Welshness. [9] According to Evans, many in the Welsh culture industry, which produces influential representations, find it impossible to imagine forms of Welsh identity that move beyond the ancient images of the “two truths”. [10] In this sense, Welsh identity is in crisis, unable to uncouple itself from outdated stereotypes that are increasingly disconnected from much of contemporary Welsh reality.

At the same time, there are signs that new, more inclusive forms of identity struggle to replace those persistent ideas, and new forms of being Welsh and in that sense of Welshness emerge. The independence movement and Welsh music are thriving (in very different musical genres, far beyond the “traditional”), according to Evans. [11] In addition, the language-learning app and research company Duolingo reported in 2021 that Welsh has become the fastest-rising language in the UK. [12] These developments enable the potential of Welsh identity to become more diverse and open. Sport is another important field here: As Evans puts it: “The Welsh football team – working-class, black, white, English-born, Welsh-born, Welsh-speaking, English-speaking – embody what new, organic forms of Welshness could be”.[13]

In the Dylan Thomas Centre, the Welsh poet’s life, works and his connection to Wales are exhibited. What kind of Welsh identity is portrayed throughout the exhibition and in the centre itself – and by what means? Based on a visit to the exhibition in the centre, combined with a conversation with two of the employees working there (and also considering a review of the museum’s previous exhibition [14]), I will try to answer these questions.

The Dylan Thomas Centre is located in a house that fulfilled many separate roles throughout its history. Once the local town hall, it became Swansea’s municipal Guildhall afterward. The building was closed in 1982 and stood empty for over ten years, as I learned in the Interview. Then, in the 1990s, it was reconstructed to function as the House of Literature during the UK Year of Literature. Since 1995, it has been operating as The Dylan Thomas Centre. In 2014, the centre was able to redesign the permanent exhibition about Dylan Thomas thanks to funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Swansea Council. Today, it holds the only permanent exhibition on Thomas in the world, and it also operates as a home to the city’s literature and arts program. The centre offers workshops available for all generations. In those workshops, contemporary writers and artists around the area teach their craft[15, 16]

The permanent exhibition dedicated to Thomas, located on the ground floor of the centre, is named “Love The Words”. The space includes a temporary area with displays that change every six months (see figure 2) and an activity room, which is open to the public. The exhibition is designed interactively, using not only text but also audio and film. A timeline guides the visitor through Dylan Thomas’ life and works. It is accompanied by a “people’s trail” that mentions significant people who have influenced Thomas and his works. Children can entertain themselves on a playfully designed children’s trail.

Two employees who kindly offered to answer my questions about the exhibition told me that one of the main goals of the exhibition was to make it “as accessible as possible”.[17] Accordingly, the exhibition is free of charge, and it is physically accessible through being on the leveled ground floor. There also is an easy-to-read version of the leaflet. Another main goal is the “promotion of Welsh literature” through the exhibition as well as workshops.[18]

Right at the beginning of the exhibition, Dylan Thomas’s local upbringing is mentioned: The first panel tells of his “happy childhood in the middle-class Uplands area of Swansea”. The same panel also mentions that he and his sister did not speak Welsh but heard it when visiting family. Dylan Thomas thus embodies a version of Welsh identity that is not directly connected to the use of the Welsh language. Being Welsh does not always mean being able to speak Welsh – in fact, only 17.8 per cent of today’s population speak Welsh, in Thomas’s time, it was 31.7 per cent. [19, 20] Today, one in six residents of Swansea speak Welsh.[21] This shows that defining Welshness primarily through the language cannot be considered as inclusive – especially when looking at contemporary developments. The centre’s employees told me they never felt excluded because they do not speak Welsh. However, they also told me they had heard different experiences from their acquaintances.

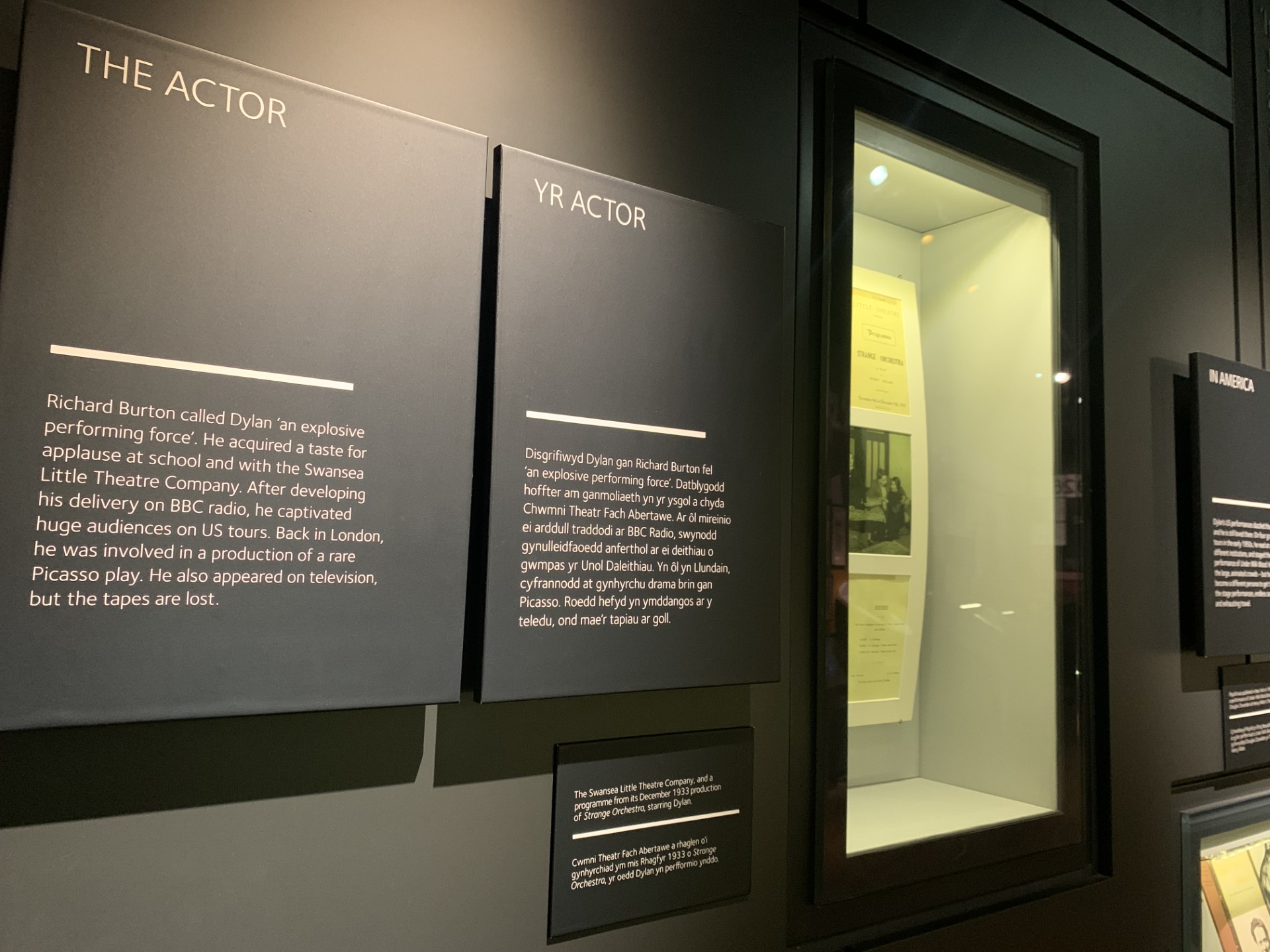

Consistent with today’s language policy in Wales, the exhibition’s texts are presented in English as well as Welsh (see figure 3). Through official language standards, the Welsh language is promoted and is ensured that it is treated equally to English (Welsh language standards). In practical terms, this complicates external communication, said one of the centre’s employees: Everything needs to be translated by a translation unit, which, for example, makes spontaneous posts on social media near impossible for them.

The exhibition focuses solely on Dylan Thomas. In the words of Lonie, who reviewed the permanent exhibit when it opened: “The exhibit successfully weaves the tale of a man who has become a symbol of Welsh culture itself.” [22] Even though the reviewer talks about the old exhibit, I would argue that it is true for the new one as well. This also means that since Welsh literature is represented through his persona, it is constricted by male connotations. The enduring stereotypes of Welsh identity are basically images of men. In the exhibit, this male-centric view is to some extent disrupted by the “people trail” that highlights the women who had an impact on Thomas throughout his life.

I was born in a large Welsh town […], crawling, sprawling by a long and splendid curving shore.

– Dylan Thomas (1943, 1953). [23]

When I asked about the ‘Welshness’ of Dylan Thomas, the employees answered that Welsh identity was strongly reflected in his works. His poetry, even though written in English, frequently explores Welsh life. Furthermore, they say, it exhibits a distinctly Welsh character that connects it to a culture of language, literature, and music that emerged in response to the fear of English cultural domination. [24] In that sense, the exhibition presents a sense of Welshness that is not fully encompassed by the “two truths” of the windswept Welsh-speaking farmer and the soot-faced miner. Instead, Welshness is associated with creativity and artistry – which also seems to be a popular, widespread representation and self-image in Wales, perhaps the “third truth”?

[1] Dylan Thomas. 1943, 1953. Reminiscences of a Childhood. In: Quiet Early One Morning, New York 1954: 3-8.

[2] [3] Federici, Eleonora. 2006. Swansea and Dylan Thomas: The City Text and the Tourist Reader. In: Translating Tourism – Linguistic/Cultural Representations, Oriana Palusci und Sabrina Francesconi (ed.), 57-72. U of Trento.

[4-11] [14] Evans, Dan. 2022. Reconstructing Welshness – Again. In: Welsh (plural): Essays on the future of Wales: 214-230.

[13] Welsh language in Wales (Consensus 2021). 2022. Welsh Government, https://www.gov.wales/welsh-language-wales-census-2021-html (abgerufen am 30.06.2024).

[15] Lonie, Emily. 2012. Exhibition Reviews – Dylan Thomas: Man and Myth. Archivaria 73: 151-153.

[16] Interview with two of the employees 27.03.2024, Swansea.

[17] History of the Dylan Thomas Centre. 2024. Dylan Thomas Centre, http://www.dylanthomas.com/dylan-thomas-centre/history-dylan-thomas-centre/ (abgerufen am 30.06.2024).

[18] [19] Interview with two of the employees 27.03.2024, Swansea.

[20] Welsh Speakers in 1921. 2024. People’s Collection Wales, https://www.peoplescollection.wales/items/30485#?xywh=481%2C176%2C526%2C346 (abgerufen am 30.06.2024).

[21] [22] Welsh language in Wales (Consensus 2021). 2022. Welsh Government, https://www.gov.wales/welsh-language-wales-census-2021-html (abgerufen am 30.06.2024).

[23] Dylan Thomas. 1943, 1953. Reminiscences of a Childhood. In: Quiet Early One Morning, New York 1954: 3-8.

[24] Lonie, Emily. 2012. Exhibition Reviews – Dylan Thomas: Man and Myth. Archivaria 73: 151-153.

Kim Aishya Nüesch