Navigation auf uzh.ch

Navigation auf uzh.ch

Take a walk-through Swansea’s Brynmill and Mount Pleasant neighbourhoods with me. By talking to locals and noticing community symbols, I highlight aspects that shape the community’s sociocultural tapestry. This offers insights into how history, culture, and daily interactions influence these spaces.

Figure 1: A map of Swansea highlighting the neighbourhoods of Brynmill and Mount Pleasant, depicting the route of my afternoon stroll.

Urban spaces are intricate mosaics of social dynamics and identities. In Swansea, a city moulded by its industrial past, enriched by educational institutions, animated by revitalisation efforts, but also plagued by economic and social troubles, the neighbourhoods of Brynmill and Mount Pleasant offer vivid examples of how uniquely shaped communities may turn out to be despite their proximity and apparent similarity.[1] Armed with a camera, a small notebook, and the determination to conquer the steep streets, I embarked on a journey to explore these areas. My goal was to become more knowledgeable about local social identities and neighbourhood dynamics, capturing what could be observed during a half-day walking tour.

My walk began at the picturesque University of Swansea Singleton Campus. I strolled through the beautifully kept park, where lush green bushes and trees framed the paths, birds chirped, and the first spring flowers blossomed. Exiting through a small gate, I found myself on a street curving into the Brynmill neighbourhood. Narrow terraced houses lined the streets, their small front lawns cluttered with trash, and signs indicating they were available to let for students. The southern part of Brynmill exhibited a distinct pattern, with the first few streets looking identical. These were filled with small cars, and busy students exited their homes with iPads, laptops, and water bottles. My presence in the neighbourhood didn’t seem out of the ordinary; people I encountered smiled at me and, in a typically Welsh manner, started conversations. The friendly interactions made it easy to get a feel for the local atmosphere.

In the five conversations I had with students and other locals, one topic recurred: the clear distinction between “locals” and the large student population in the area, which currently numbers more than 8000 students.[2] Many students mentioned that the southern part of Brynmill was reserved exclusively for students and is subdivided into two categories: Welsh students and internationals, which include the English. This duality leads to ongoing tensions and conflicts. According to locals, student protests have occurred since the 1980s due to grievances about favouritism, living conditions, tuition fees, and rent.[3] The most southern part of Brynmill hasn’t changed much since then; some houses remain in desolate condition, with house owners neglecting maintenance, resulting in properties plagued by mold, slug infestations, and overall neglect. The common perception is that student housing often comes with declining quality of the housing stock, which students tend to accept quietly, believing it’s not worthwhile to raise concerns, given the temporary nature of their stay[4].

These occurrences seem to have negatively affected the sense of community within Brynmill. All locals I met, especially the elderly, spoke of a loss of cohesion and increasing fragmentation of the social structure. I am tempted to see the conditions of the houses as evidence of this – and also the way these locals speak about the students. As one interview partner noted, “We used to know all our neighbours, but now they change every semester”.

Interestingly, older locals who live in the northern part of Brynmill, as well as a few shop owners who have lived in the area for generations, spoke about the students enrolled at Swansea University as being their neighbours – and referred to themselves as lifelong and true students of the University. It appears that some residents of Brynmill, especially among those who have lived there for many years or even generations, tie their identity not only to the neighbourhood but also to their affiliation with Swansea University. For them, being a local is synonymous with being part of the University: “Generations of my family have been living here – we are the students of Swansea University and will forever be, it doesn’t matter if you actually attended the University over there – it matters if you are a resident here”.

In urban sociology and anthropology, the concept of "Urban Villages" refers to tight-knit, community-oriented neighbourhoods within urban settings that function similarly to traditional villages. These areas are characterised by strong social ties, local identities, and a sense of belonging among locals, despite being part of a larger, often impersonal urban environment. [5] This concept elucidates how small communities sustain their distinctive identities and social cohesion within an urban environment. I found evidence of this phenomenon particularly among the older local residents I encountered during my walk, as exemplified below.

While talking to inhabitants of Brynmill, I noticed another recurring theme – one that appeared in every conversation there: The people I spoke to proudly emphasised how their neighbourhood differs from others in Swansea, especially Mount Pleasant. Distinguishing themselves from Mount Pleasant seemed to be a significant part of their local identity. Topographical descriptions such as “up and down,” “wedged on the hill,” and “looking down to the base” evoke a sense of spatial hierarchy and social stratification between the neighbourhoods. These terms suggest not only physical elevation but also perceived class distinctions – with Mount Pleasant in the role as the “higher-up”, privileged area – which was observed somewhat sceptically from the viewpoint of Brynmill. This perceived disparity was evident, for example, in a conversation with a lady at a local bakery shop, which has been run by her family for generations. She proudly mentioned that many residents of Mount Pleasant come down to purchase her Welsh baked goods. This patronage seemed to confer a sense of honour and validation, highlighting the social prestige associated with this approval. These pastries were separated by a block of wood from the international bakery goods she offered. “These are the ones for the residents, the true students,” she said, pointing to the Welsh pastries with a proud look on her face. “The others are for the picky internationals – the English,” she added, pointing to the other side of the wooden block. When I raised my camera to take a picture, she gave me a stern gaze and shook her head. Respecting her wishes, I left the bakery, jotted down my notes, and checked my phone’s map to find the quickest route to Mount Pleasant. Determined to make the steep uphill trek, I was soon met by a hailstorm and rain, which gave me a moment to pause and reflect on what I had experienced so far.

I rescued myself in a coffee shop where I met fellow UZH students who had also fled the weather. A hot tea and some discussions later, I made my way up to Mount Pleasant. Unfortunately, I was not able to interview any locals and talk about how these symbols serve as an expression of community and resistance to external influences. But I tried to make sense of what I saw with what I knew. In contrast to Brynmill, Mount Pleasant seemed to be more of an upper-middle-class area – and one where students did not have such a strong presence.[6]

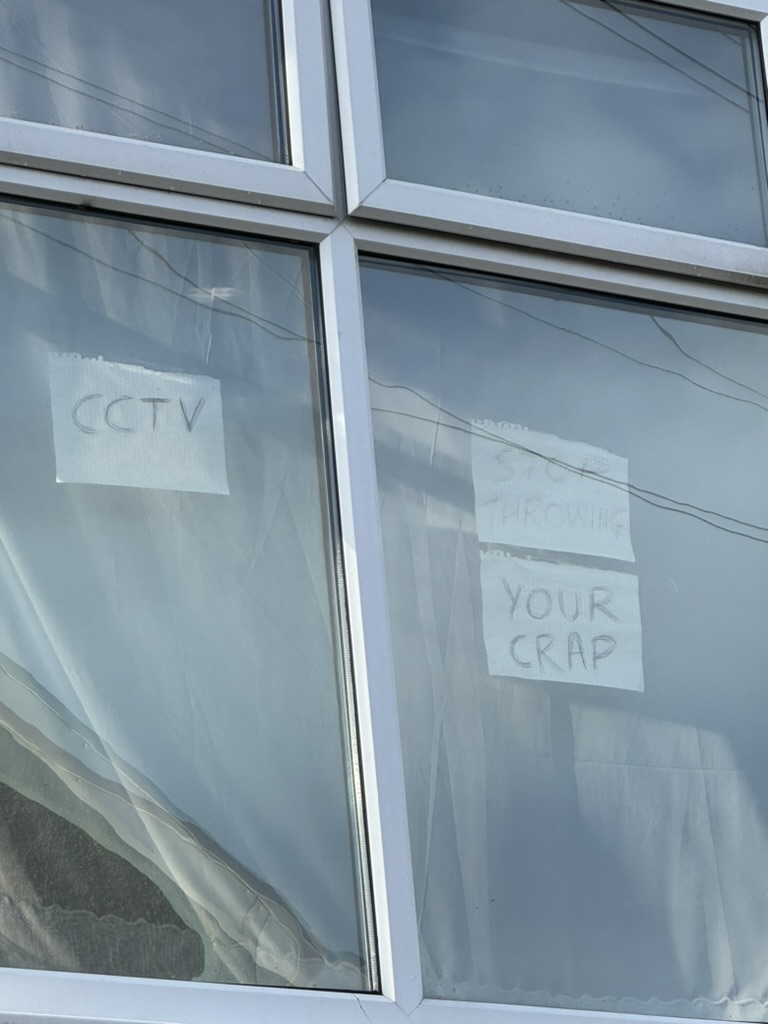

The streets were tidier, and almost every house had a beautiful view of the sea. The further up I went, the more security cameras I saw, along with high gates and more expensive cars. (See Jan Kohler's report for more information about the safety narrative and its manifestations in Swansea). Here, it felt surprising when I encountered a house with a lot of trash bags in front. On the opposite side of that house, there was a colourful mural saying, “Let’s keep Mount Pleasant, pleasant.” It was carefully handcrafted, seemingly a community project. There were no city labels or anything that indicated that this was an appeal from the city administration to the residents. This was not the only mural I encountered throughout Mount Pleasant. There were more murals that looked the same on every other street I walked by. Several stickers on lampposts and notes on windows appealed to the community with the same message: Keep the trash and untidiness out of Mount Pleasant! It seemed like a redundant, moralising message.

Mount Pleasant’s visual landscape is marked by community symbols. Graffiti, stickers, and public artworks seem designed to reflect the cultural identity and pride of the residents. A resident of Mount Pleasant whom I met by chance the next day told me that the artworks (murals and stickers) were “our way of telling our story and showing that we stand together.” They not only acted as identity markers but also strengthened the sense of community and solidarity within the neighbourhood. Read more about Welsh Identity and the role of Dylan Thomas in Kim Aishya Nüesch's article.

Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the social production of space posits that space is not merely a physical container but is actively produced and shaped by social relations and practices. He argues that space is created through the interactions and power dynamics among individuals and groups, reflecting and reinforcing societal structures and ideologies. This theory highlights how urban environments are continuously constructed and reconstructed through everyday social processes and interactions. In this context, the efforts to maintain a cleaner neighbourhood serve to strengthen communal bonds and simultaneously stress local boundaries, illustrating how the production of space is a continuous social process that reflects – and shapes – residents’ values and priorities.[7] Although my observations alone cannot definitively conclude that this sentiment is shared among the residents, the pervasive presence of these cleanliness initiatives suggests that they indeed reflect a widely shared priority within the community.

My ethnographic stroll concluded at the bottom of Mount Pleasant, where I reached the main road leading into the city centre. Along the way, I observed numerous signs and symbols and wished to speak with locals about their significance, but I encountered no one. Despite expecting more foot traffic, the streets were empty, likely due to the abrupt weather change, even though the area appeared to be a rather suburban, affluent neighbourhood.

Nevertheless, I drew some conclusions and believe that my observations can provide a foundation for further inquiries. While Brynmill seems to be defined by the divide between locals and students (and between the Welsh and the internationals within the latter), Mount Pleasant seems to be characterised by a stronger, but also more exclusive sense of community and symbolic identity markers that differentiate it from adjacent areas. Both neighbourhoods appear to showcase how local identities and social structures are uniquely shaped in urban spaces. It would be interesting to delve deeper into both neighbourhoods or compare other neighbourhoods in Swansea to better understand how local urban identities are formed and how relevant they are to the inhabitants.

Reflecting on my observations, it becomes apparent that Brynmill and Mount Pleasant are more than just neighbourhoods; they seem to be dynamic communities shaped by their histories, cultures, and social connections. Each street and conversation contributes to the tapestry of urban life, raising the question which multifaceted identities may define these areas. The visible contrasts between these Swansea neighbourhoods—observed in their social structures, local pride, and communal symbols—hint at the diverse ways in which space is experienced and valued. This exploration also underscores the potential importance of recognising and preserving the distinct identities that contribute to a city’s mosaic. Future research could look at these complexities, asking how urban identities are formed and how significant they actually are for residents. For me, this small journey has provided a tentative appreciation for the balance between traditions and change, and the interplay of community and individuality, that characterises urban landscapes. Neighbourhoods exemplify the dynamism of urban life. As I conclude my exploration of these streets, I depart with a deeper appreciation for the interplay of community and culture. Swansea reveals itself as a city where every corner tells a story.

Cheers to Swansea and the journey it offers!

[1] https://www.swansea.gov.uk/article/9582/Regeneration-and-development-plans-and-policies

[2]https://www.digsswansea.biz/reasons-to-live-in-brynmill-as-a-student#:~:text=Brynmill%2C%20with%20its%20mix%20of,over%208%2C000%20students%20living%20there

[3]https://swanseauniversitystudentunion.wordpress.com/1980s/https://swanseauniversitystudentunion.wordpress.com/2000s/

[4] https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/lloyd-harris/swansea-student-housing_b_8164996.html

[5] Lindner, Rolf. Die Angst des Forschers vor dem Feld: Über die Widersprüche der ethnographischen Erfahrung. Frankfurter Verlagsanstalt, 1998. S.147-171.

[6] The statistical data available primarily pertains to Uplands, the county encompassing Brynmill. Similarly, Mount Pleasant is situated within Castle County. The data does not provide a more granular classification within these counties. Consequently, it is not feasible to ascertain the presence or distribution of middle or upper-class populations based on the provided information, as the socioeconomic composition varies within each county. https://www.swansea.gov.uk/caprofiles

[7] Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith, Blackwell, 1991, S. 68-80.

Serafina Andrew