Navigation auf uzh.ch

Navigation auf uzh.ch

Dare to follow me down the rabbit hole, and set out with me on a noble quest to locate traces of myth within the post-industrial South of Wales. Remember to keep an eye out for faeries and dragons lurking around the corners of Swansea or Cardiff, and prepare to brave any weather condition on your journey through the UK’s second smallest country – from heavy downpours accompanied by freezing gusts of wind to unexpected hailstorms. Perhaps you’ll even get the chance to experience what has been shown to us on the screen and temporarily get lost between misty hills of faded green, and discover a passage to a place outside of the ordinary. Cross over into a fantastical realm, wander through ancient forests inhabited by dark spiritual forces, and look for remainders of the so-called ‘Mythic Wales’ – a fictitious, medialised space inspired by Celtic-Britonnic tales of old, and more specifically: the Mabinogion.

Figure 1: A selection of screencaps taken from different Welsh films.

A bleak and washed-out scenery, covered in mist, stretches out in front of our eyes, with a dimly lit humanoid silhouette emerging from the grey, slowly approaching the audience on the other side of the screen. Undoubtedly, modern movies set in Wales[1] – most commonly located within the genre of speculative fiction – paint a sinister picture of a harsh, uninviting as well as arcane landscape reminiscent of grim-dark spaces where the fantastic crosses paths with the uncanny. Weaving together elements of folklore, gothic horror and Welsh mythology dating back to the high middle ages[2], contemporary English-language films that take their characters on a voyage to Wales tend to portray the country as a mythic, and more importantly, transitory place – where past and present, self and other, the real and the imaginary merge into one.[3]

Stepping off the train in Cardiff and heading for the bus that would take me towards Swansea, further along the coast, the view in front of me – I have, obliviously, fantasized about lush pastureland and picturesque castles taken straight out of an Arthurian romance film – leaves much to be desired. Instead of vast meadows shrouded in fog and mystery that encourage travelers to enter a magical domain, it is plain brick houses as well as high-rise buildings that populate the background and welcome me to Cymru. A moment of disillusionment washes over me, as I expected to set foot into the rural Shire only to get stranded in the industrialized pits of Isengard.

Later, strolling through the streets of Swansea for the first time, peeking at spray-painted walls of crummy, run-down houses, as well as fenced-in construction sites, the abyss between expectation and my own perceived reality becomes more pronounced by the minute. As I reach Swansea castle – ruinous remnants of a medieval fortress that withstood even the Blitz, the German bombardment – my notion of Wales has already undergone multiple adjustments, and I find myself wondering about the dissonance between what is right in front of me and what has been presented to me on-screen. And while I am, of course, aware of the fact that I am neither an expert on the matter, nor is the region of South Wales representative of the country as a whole, it is fascinating to me that the industrial revolution – in spite of its historical significance – has, from what I’ve been able to gather prior to our trip, practically been absent from Welsh filmmaking altogether.[4] While coal mining, as a crucial factor contributing to the nation’s sense of identity, has found its way into visual narratives, predominantly crafted by non-Welsh directors[5], the majority of films produced within the borders of Wales have refrained from going down that road.

Instead, much of what is portrayed on celluloid – in well-known Welsh-made films the likes of Gwen (William McGregor, GB 2018) or The Apostle (Gareth Evans, GB 2018) – takes after a glorified and nostalgia-fueled pre-industrial past[6]: a fictitious and strictly agricultural ‘before’ that is rooted in early Welsh myths, namely the “Mabinogion”. Transcribed and translated into English by Lady Charlotte Guest in 1840, the 11th century-based Mabinogion consists of eleven Welsh prose tales drawing on early Celtic-Brittonic storytelling traditions and incorporating elements of myth, folklore and history.[7] Said to have been passed down through the decades and generations by bards travelling the lands, who spread these stories by word of mouth, the medieval text, in its written down form, ranges from eerie voyages through the realm of the ‘Otherworld’ and uncanny faerie encounters to chivalric romances and failed attempts to locate the Holy Grail. Scooping into a wide array of themes, the Mabinogion is thus nothing short of invigorating adventures.[8]

⇒ learn more: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mabinogion

This multi-layered collection of stories has been translated into different forms of media in recent years, most notably visual. Loosely based on this anthology of Welsh legends, the South-Korean online role-playing game “Mabinogi”, for example, grants its audience access to a mystical land where one can join heroic quests or stride into epic battle.[9] On a cinematic scale, there have been a few modern takes on the medieval text compilation as well, although these films hardly received any attention outside of Wales. More often than not, such movies met their fate quickly due to little funding or limited resources in general.[10]

This is a more general issue for Welsh films. Although comparably well-known and successful Welsh co-productions the likes of The Apostle (Gareth Evans, GB 2018) or Pride (Matthew Warchus, GB/FR 2014) made it to the big screen or a streaming service such as Netflix, the majority of Welsh movies released thus far have remained somewhat hidden from the global public’s eye. Quite poetically so, one might argue, for these films seem to frequently center on what has previously been out of sight and has now come to be revealed for a short period of time. Nevertheless , as of 2024, there are funding schemes meant to aid and encourage local screenwriters, directors and others wanting to earn a living in the Welsh film and tv industry.[11]

Hence, if one knows where to look, there is certainly a recurring tendency to be detected: A large number of these movies not only draw upon themes and narratives taken directly from the Mabinogion – usually employing the ambiguity of dread and enchantment that is inherent to the fantastic[12] – but they just as frequently address issues of communal identity and national belonging as well as a sense of (dis)place(ment).

Catering to cinephiles with a passion for (folk-)horror, British films set or produced in Wales such as The Dark (John Fawcett, GB 2005) utilise ideas of liminality, uncertainty and anxiety by both spatially and spiritually trapping their characters in-between reality and a nightmarish ‘other(world)ly’ realm filled with strange and supernatural beings.

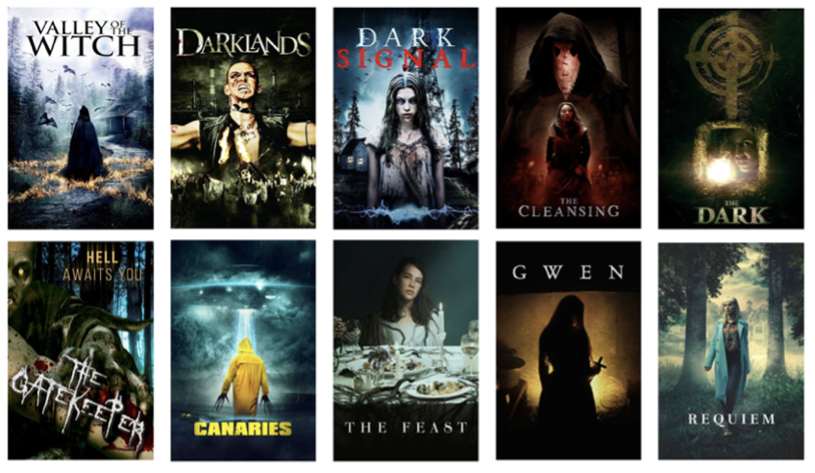

Figure 2: A selection of Welsh-produced movies leaning into the mythic. [13]

Ingrained in these stories is the characters’ ever on-going quest for belonging, as well as their attempt to navigate between their past and present, tradition and change. Geographically located at the margins and thus difficult to reach, Wales – in its medialised version on the screen – is frequently depicted as a bridge allowing its visitors to cross over, leaving behind the ordinary, and transcending to the mystical unknown.[14] One does not have to look any further than this random line-up of Welsh movie posters (see: Figure 2) outlining a visual, as well as thematic, affinity for the occult: Wiccan group gatherings in remote forests, the meddling with demonic forces hidden away within the darkest corners of the Welsh countryside. Jokingly, the official tourist information site of Wales even claims that such a cinematic preference for the uncanny stems from the fact that the US-produced cult classic film The Wolf Man (George Waggner, US 1941) chose their country as a backdrop, and therefore paved the way for the Welsh to create their own cabinet of horror flicks.

⇒ learn more: https://www.wales.com/about/culture/marvellous-welsh-movies

Exploring the paranormal and inexplicable through a mythology-tinted lens and tapping into tales and motifs from the Mabinogion, modern films produced in Wales fabricate their own iteration of a Celtic country that has been overshadowed by its larger neighbours for centuries, but is now being granted a certain screen presence. Welsh filmmakers delve into their native country’s cultural heritage and (re-)medialise stories of old for a new generation. Welsh-language horror flicks such as the most recent Gwledd (Lee Haven Jones, WA 2021) have debuted at international film festivals aimed at a non-Welsh speaking audience, spreading the word: in a minority language, no less.

All of this raises the question: what sort of narrative is construed, or rather; replicated in such tales that repeatedly illustrate Wales as not only a liminal space, where the fantastic joins forces with the uncanny, but as a seemingly timeless, indistinct place which solely exists in fiction? Does this perhaps reflect a willingness to play into, and reinforce, stereotypes about Welshness – and if so, which ? Or could it be an effort to reclaim a part of cultural heritage that has, in the past, been attributed to a larger Celtic-Britonnic tradition, but not been marked as explicitly Welsh? Taking into account that the quest for belonging and the search for identity is a recurring theme within these narratives[15], one might be tempted to argue that – through such storytelling – Welsh filmmakers themselves are perhaps trying to offer answers to those questions. «Myth gives meaning to existence»[16] after all. Exploring the concept of a Wales shrouded in magic and mystery existing outside of our understanding of time and space and following its own laws dating back to the Mabinogion may give «to Welsh people a sense of belonging»[17] and to Welsh filmmakers an opportunity to both keep such myths alive and breathe new life into them through a modern-day lens.

In their article about the medialisation of Welshness, Audrey Becker and Kristin Noone draw a distinction between the actual country and its literary and cinematic alter ego: ‘Mythic Wales’ refers to a fictionalised version of the Welsh nation and its people that is aesthetically and thematically inspired by the Mabinogion, as well as other Celtic legends.[18] Traces of such an idea of a Mythic Wales can once again be discovered on the official tourist information website that demonstrates that «Welsh history has a deep mythic overlay»[19], highlighting North Wales with its beautiful landscapes, and exhibiting their impressive castles of old, as well as promoting a variety of trekking paths, one might expect to see in a Lord of the Rings movie. Speaking of Tolkien – and this certainly goes to show just how much our expectations were tainted by the cinematic ‘Mythic Wales’ – the link between Wales and The Lord of the Rings – or fantasy fiction in general – was brought up during our first group session back in March when we had to spitball and scribble down terms we intuitively associated with Wales.

Although my first impression did not immediately match what I had thought would await me there, I eventually came around and began to understand why the dominant genre in Welsh filmmaking is a mixture of folk-horror, the gothic and the fantastic. Judging from the weather conditions alone: somber skies and a scenery made out of different shades of jaded brown, green and grey (see: Figure 3) certainly evoke an atmosphere that fits narrations of an encounter with a sinister creature from another realm, or some ritualistic human sacrifice made to an ancient god(dess) deep in the woods. Despite us staying in South Wales and focusing on the industrial aspect, the mythical nonetheless seemed to be implanted in our surroundings. Not even a stone’s throw away from Swansea, we would drive by fields untouched by the industrial, where grazing sheep or horses, standing dangerously close to the road, would stare at us, unbothered by our presence. Within the city walls of Cardiff or Swansea, meanwhile, it turned out impossible not to bump into at least one variation of the heraldic charge of the red dragon. As a creature derived from mythical tales of heroism usually set in a land outside of reality’s rules, the symbol of the dragon carries with it a national pride as well as an emblematic connection to the fantastic.[20]

The way I experienced it, the mythical I was so eager to cross paths with, would emerge from behind the urban every now and again, reminding us of its (continuous) extistence. The perceived dissonance that aroused my curiosity on my first stroll through the streets of Swansea, would especially make an appearance whenever we drove from one town to another. As briefly alluded to earlier, we would spot untethered farm animals peacefully grazing by the side of the road, but as soon as we would switch seats and glance out the other window, the view would drastically change to e.g. the Moloch-shaped silhouette of Tata Steel. Moments of such stark contrast would raise the aforementioned questions regarding cinema – Welsh-based and global – not only contributing to the mythologisation of Wales but also down-playing real-life social issues – notably (the current lack of) job opportunities as well as employment security affecting the South[21] – in favor of a romanticised, dream-like version of Wales, depicted as a pre-industrial, magic-infused idyll neither real nor equal to present day Wales.

[1] I am referring to both Welsh-produced movies and non-Welsh-produced movies here, since it can be difficult to separate the two entirely: plenty of so-called ‘Welsh-produced’ films are either British co-productions or projects that heavily rely on funding from the UK and other European countries or even the United States.

[2] Vgl. Johnson on Historic UK (https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofWales/The-Mabinogion/)

[3] Vgl. Sullivan, C.W.: Welsh Celtic Myth in Modern Fantasy. New York: Greenwood Press, 1989, 4f.

[4] Here I am exclusively referring to movies set and produced in Wales that are directed by Welsh filmmakers who tell the story of their country and their people.

[5] One notable example is of course the cinematically released British/French co-production Pride (Matthew Warchus, GB/FR 2014) which specifically addresses the importance of the industrial revolution within the South of Wales as well as the miners’ strike taking place in 1984/85.

[6] Vgl. Becker, Audrey und Kristin Noone (Hg.): Welsh Mythology and Folklore in Popular Culture Essays on Adaptations in Literature, Film, Television and Digital Media. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2011, 3f.

[7] Vgl. Filmer-Davies, Kath: Fantasy Fiction and Welsh myth. Tales of Belonging. London: Macmillan Press, 1996, 155.

[8] Vgl. Filmer-Davies, Kath: Fantasy Fiction and Welsh myth. Tales of Belonging. London: Macmillan Press, 1996, 155f.

[9] Vgl. Becker, Audrey und Kristin Noone (Hg.): Welsh Mythology and Folklore in Popular Culture Essays on Adaptations in Literature, Film, Television and Digital Media. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2011, 2f.

[10] Vgl. Blandford, Steve (Hg.): Wales on Screen. Wales: Seren, 2000, 14.

[11] For more information visit: https://www.wales.com/about/culture/marvellous-welsh-movies

[12] Vgl. Sullivan, C.W.: Welsh Celtic Myth in Modern Fantasy. New York: Greenwood Press, 1989, 9.

[13] Of course, this line-up of Welsh-produced movie posters is not a definitive list. My selection was, first and foremost, influenced by A) the accesibility and availability of these movies online and B) how similar they were to each other at first glance, aesthetically speaking (e.g. lighting, color palette, visual motives such as trees or symbols of the occult, etc.).

[14] Vgl. Becker, Audrey und Kristin Noone (Hg.): Welsh Mythology and Folklore in Popular Culture Essays on Adaptations in Literature, Film, Television and Digital Media. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2011, 3.

[15] Vgl. Filmer-Davies, Kath: Fantasy Fiction and Welsh myth. Tales of Belonging. London: Macmillan Press, 1996, 26.

[16] Filmer-Davies, Kath: Fantasy Fiction and Welsh myth. Tales of Belonging. London: Macmillan Press, 1996, 3.

[17] Filmer-Davies, Kath: Fantasy Fiction and Welsh myth. Tales of Belonging. London: Macmillan Press, 1996, 26.

[18] Vgl. Becker, Audrey und Kristin Noone (Hg.): Welsh Mythology and Folklore in Popular Culture Essays on Adaptations in Literature, Film, Television and Digital Media. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2011, 3.

[19] Filmer-Davies, Kath: Fantasy Fiction and Welsh myth. Tales of Belonging. London: Macmillan Press, 1996, 2.

[20] Find out more about the meaning of the dragon in Jana’s article: Link.

[21] Find out more about the current (un)employment crisis in the South – Port Talbot, in particular – in Milena’s article: Link.

Zulaima Carla Ratto