Navigation auf uzh.ch

Navigation auf uzh.ch

As the largest steelworks in the UK faces the imminent shutdown of both its blast furnaces, Port Talbot residents are confronted with a future filled with uncertainty. How has the town's industrial past shaped community identity and gender roles? How are young people in Port Talbot perceiving and responding to the changes in their town?

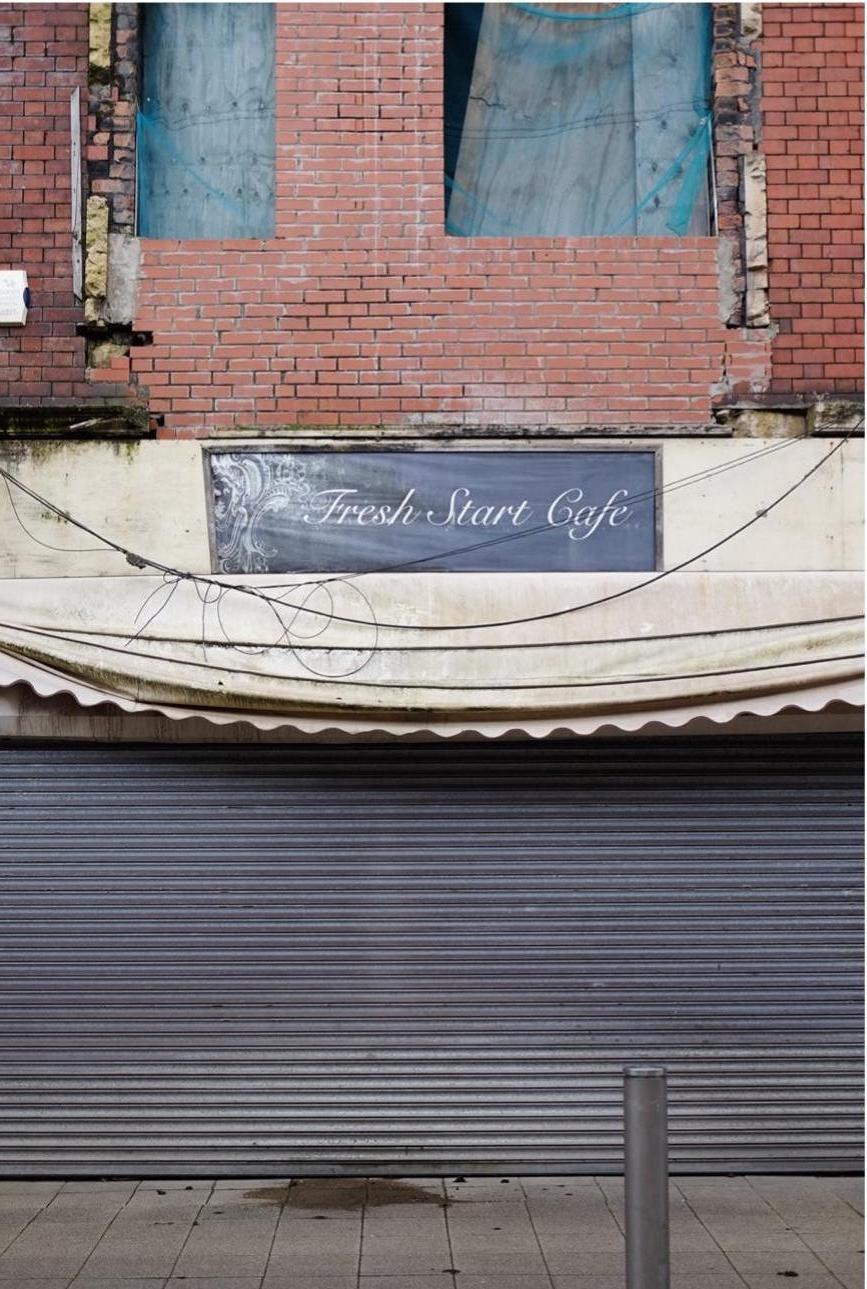

Figure 1: Photo by Milena Schmid.

"The closure of the blast furnace will cause so much unemployment. So many people in this area depend on the steelworks. The atmosphere in Port Talbot is very, very bad. There is a lot of fear in the community", the taxi driver in front of us says on the way from Swansea to the steel town. We are sitting on the back bench of the car, looking out of the window and we can see the steelworks from afar. Giant industrial buildings, chimneys and billowing smoke cover large parts of the outskirts of the town. “Of course, there's the issue of pollution on the other side, that's important too,” she continues. “But a focus on greener steel production should not come at the expense of so many people losing their jobs in the coming months.” The fear and uncertainty of people in Port Talbot and the feeling of having been let down by the UK government is something we will hear again and again in the days to come.

We had first heard about Port Talbot, this small industrial town in South Wales, during the first preparatory meeting for our excursion to Wales.

South Wales has a rich history of coal mining and steel production. These industries were not just economically important, they also shaped the social life of communities. The decline of these industries left profound gaps, not just in employment, but in the community’s identity and way of life. We thought we could sense this feeling of decline even in Swansea, where everything felt a bit ‘left behind’, and it seemed even more pronounced in Port Talbot.

Port Talbot is home to the largest steelworks in the UK and one of the largest in Europe, owned by Tata Steel Ltd since 2007. Many residents in the area depend on the plant as their main sources of income. In late 2023, Tata Steel Ltd. announced plans to close both giant blast furnaces in the course of 2024 to transition to greener steel production, for which scrap metal will be recycled. This closure will result in 2,800 workers being made redundant, with additional job losses expected in related industries.

In the next preparatory session, we looked at older ethnographic research that analysed the impact of steelwork closures on communities similar to Port Talbot. Valerie Walkerdine and Luis Jimenez (2012) conducted research in an anonymised town in South Wales whose steelworks closed in 2002. They found that the loss of work profoundly affected people’s lives in the community with impacts closely intertwined with questions of gender.[1]

As Walkerdine and Jimenez write, men worked in the physically demanding and hazardous jobs of the mines and steelworks, while women were predominantly assigned domestic roles, maintaining and symbolising stability and support for their families. This dynamic created a specific idea of masculinity tied to industrial labour which is characterised by attributes such as toughness, strength, stamina and camaraderie. The closure of mines and steelworks in the 1980s led to massive unemployment. As men lost their jobs, the traditional gender roles within households and communities became unstable as well. This is why de-industrialisation created not only an economic shift but also a cultural and social one. The social identity of men and women had to adapt to new realities. It was difficult for men to find new well-paid industrial jobs, and other fields of work that many considered ‘more feminine’ were often not compatible with their gender identity. For women, this meant navigating a dual burden of managing households while also seeking employment in a challenging job market. The struggle for employment saw them accepting low-paid, insecure jobs, often in the service or care sector. Moreover, they had to support their husbands mentally, as the latter often plunged into deep psychological crises due to the loss of their work-based identity and pride. Many interviewees told Walkerdine and Jimenez that they felt trapped and that they had lost all prospects for the future.[2]

This lack of perspective affected us strongly while reading the book chapters, and it seemed natural to wonder whether similar things could be witnessed in Port Talbot. At the same time, we thought that these perspectives might be too one-sided and bleak. Weren’t there, for example, young people who were able to shape their future independently of their hometown? We felt the need to get in touch with young people from Port Talbot to hear about their experiences.

To do so, Milena downloaded a dating app already before our excursion and made clear on her profile that her search for contacts was based on research interests. Shortly afterwards, she had a ‘match’ with Dylan (name anonymised), a university student from Port Talbot. As an artist whose work is concerned with the future of his hometown, he was very interested in an exchange. They wrote to each other in the days before the trip, she sent him the ethnographic research papers we had discussed – he was interested in what we read about his area – and he told her about himself and his perspective on his town. He explained how deeply his own identity was linked to Port Talbot and why he felt compelled to defend the town against negative portrayals by outsiders who often dismiss it as a ‘rough shithole with loads of drug addicts’, as he summarizes their view. Despite the challenging circumstances that impact his community, Dylan strives to highlight the beauty of the town through his artistic dialogue with the place.

During an interview conducted while walking through Port Talbot, Dylan shared his perspective on his hometown and the current situation amid impending changes. He cautioned that his account represents just one viewpoint, as others might see things differently. Yet, this encounter gave us a valuable perspective from a local of our own age group.

We walk along Station Road, a semi-covered shopping street, which was designed as part of the Port Talbot regeneration programme from the 2010s. Dylan says that as a result the town is losing its character. Also, many shops had to close since Covid. In fact, the street seems deserted. We walk past numerous ‘We are closing soon’ signs and find ourselves in front of a rather run-down building. “How ironic! Fresh start cafe”, Dylan reads the lettering above the door, “and it’s closed down”.

We then walk along a street where the houses change from run-down to increasingly ‘posh’. Port Talbot has many well-kept and some luxurious houses. When we stop in front of a white villa, Dylan says it’s funny that drug dealers and the richest man in town live in the same street. The person who lives in the villa is the opera singer Paul Potts, who won the popular TV show Britain’s Got Talent in 2007 and became an international celebrity. During Covid, he sometimes stood on his terrace in his suit, with a microphone in his hand, and filled the neighbourhood with his opera singing. From our visit in the Wetherspoon pub in downtown Port Talbot earlier, we know that there is a long and rich history of entertainment stars who were raised in the town – Richard Burton, Anthony Hopkins and Michael Sheen are the most famous.

These days, however, there is not much going on in the city – and, more generally speaking, members of the older generations claim that the ‘real’ life of Port Talbot lies in the past. When Dylan was young, he says, his grandmother used to tell him that he should have grown up here in the 1960s and 70s. Dylan says: “There was a fair on the beach. You know, it was thriving.” At that time, 18,000 people were employed at the steelworks (now there are 4,000) and Port Talbot had twice as many inhabitants as it does today. “It's like you're living in some sort of hangover of the past.” Many people Dylan knows would move away, but not him. He travels to university 35 miles almost every weekday but lives at home. “Where should I go? My family is here and it’s not easy to build a new identity in a new place.”

At one point, we stop. Dylan suggests that we turn around walk back to the city centre. He mentions that it's financially very tight at home at the moment. Due to the recent closing of the coke ovens at Tata Steel in Port Talbot, Dylan’s stepfather lost his job there. Since his qualifications are very specific to this workplace, it isn’t easy for him to find another job quickly, especially not one that is well-paid. Dylan knows that many other families in the area face the same situation: “It is like history is repeating itself with the coal mines shutting in the 80s. They have not been given any alternatives. There will be nowhere in town to match the wage of the steelworks, forcing people to travel out of the town to work, but the mass redundancy will cause a huge amount of unemployment which means everyone will be going for the same jobs which will make it more difficult to find work.” For Dylan’s stepfather, the redundancy at the steelworks was a shock. With his family depending on his income, it is unclear what will happen next. Dylan’s mother, who works in a supported living complex for homeless teenagers, tries to compensate for the loss of income. She was in Cardiff all day for a course, he says, as she now works more to make up for the loss of income in the household, up to 80 hours a week – but only temporarily.

We later wrote to Dylan’s mother to hear about her perspective. In her reply, she expressed that she suffered from the fact that her family had been so badly affected and that it was, as she put it, a very sad and depressing time for hard-working people. Dylan’s stepfather is employed as a contractor, which means that he is not employed directly by Tata, but through another company. According to him, the impact of the dismissals extends beyond the 2,800 employees officially announced by Tata Steel, affecting an additional 8,000-10,000 contractors. These contractors, like him, are often left without any compensation.

In the meantime, we have walked up a small path and are now leaning against a railing with an overview of the motorway and the sublime steelworks in the distance. “There will be a change in the town, also visually, after the closure of the blast furnace. Everything will change.” Dylan talks about how beautiful the steelworks look at night when the fires are burning. The dystopian science-fiction film Bladerunner (D: Ridley Scott, 1982) was inspired by this. Dylan says: “There is a very strange connection between the past and the future at the moment now. It’s a fact that this town is holding on to some sort of identity from the past and is struggling to actually go into the future. It’s like in a limbo state in between the two, it’s strange. This specific time, the year that everyone gets fired from the steelworks. It’s so hard to picture a future. Like, when you ask me, how do I see the future of, I really don't know. I’m trying to base the future on what has happened to certain towns, similar things that have happened. I’m just assuming that it’s going to go the same way as in Ebbw Vale, a small Welsh town that relies on a primary employer. The employer gets ripped out, and what happens then is, it goes into decline, doesn’t it? Slowly declines into destitution.”

We gaze silently at the city in front of us for a while and, looking behind us, we see that dark clouds have gathered. Standing close to the motorway, we suddenly see an entire house pass by on a trailer. “Oh, that's my nanny’s house. Getting stolen with my grandmother in it,” Dylan comments sarcastically, the scenario feeling all too fitting. As he walks us back to the station he says: “Although many people are moving away. I’ll stay. Port Talbot is my home.”

Back at home, we try to put Dylan’s statements into context. The situation depicted during our visit shows several similarities with what Walkerdine and Jimenez presented in their work. The stepfather, working in Tata Steel Limited – as did his father and grandfather – lost his job with little hope of finding a similar job. Dylan described to us his state of mind after the redundancy as a loss of identity. The mother works in the care sector, now taking up more work – a very high number of work-hours – and is compensating her partner’s lost income. Dylan’s brother is working, now self-employed, as a plasterer, a traditionally “masculine” labour. Both work environments underline the gender specific roles depicted by Walkerdine and Jiminez work

Besides these similarities, however, we can also see differences from the main narrative of the study. For example, Dylan’s stepfather was revising his CV and looking for a new job the same week he was made redundant. Despite Dylan’s statements, it seems that he wasn’t completely stuck in the “limbo state”. Furthermore, quite a few people in the new generation that grew up in Port Talbot, including Dylan, had not taken up work in the steelworks in the first place – there have not been that many jobs in quite some time, due to previous waves of rationalisation. Dylan studies music and is currently working on a project portraying Port Talbot. His biological father is also a musician who manages to make a living out of this artistic occupation. Conditions like these would allow Dylan to leave Port Talbot and build a new future for himself – if this is what he wants.

Furthermore, the sense of community, which we came across quite often in our readings and also in encounters with people in South Wales, was not so obvious to Dylan. He says he rather feels like “everyone’s in their own struggle”. At the same time, he mentioned more than once that people have a strong support and bonds within the family. Could this explain why Dylan also makes his own future so dependent on the future of Port Talbot? Perhaps fittingly, the famous Welsh term ‘hiraeth’ signifies, according to the poet Ellis Evans, “the sense of loss that comes from having been separated from one’s home; missing the feeling of being home, of having a place.” [3]

[1, 2] Walkerdine, Valerie und Luis Jimenez. 2012. Gender, Work and Community After De-Industrialisation. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1057/9780230359192, http://link.springer.com/10.1057/9780230359192 (zugegriffen: 19. Februar 2024).

[3] Walkerdine, Valerie und Luis Jimenez. 2012. Gender, Work and Community After De-Industrialisation. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1057/9780230359192, http://link.springer.com/10.1057/9780230359192 (zugegriffen: 19. Februar 2024). P.1

Elia Pianaro & Milena Schmid